From 1958 to 1962, anywhere between 17 and 55 million people died in mainland China from famine.

From 1966 to 1976, anywhere between 750,000 and 8 million died again in revolutionary violence.

In this same time period, more than forty billion volumes of political writings by the country’s paramount leader were printed and recited across the nation.

The variation in these estimates does not explain (but is perhaps explained by) the ongoing absence of these massive historical traumas from public memory and discourse, both in mainland China and beyond its firewalls. Nor do they explain how such astronomical physical and intellectual privation could have been possible.

The figures and stories from those decades seem so high as to be absurd, stranger than fiction. Could it really be true that so many people starved to death? That students beat their teachers to death? That a single man could have been so revered? And what would it mean to attempt to imagine how all this could have been, over forty years after the fact, when we have supposedly left all this hunger, violence, and fanaticism behind?

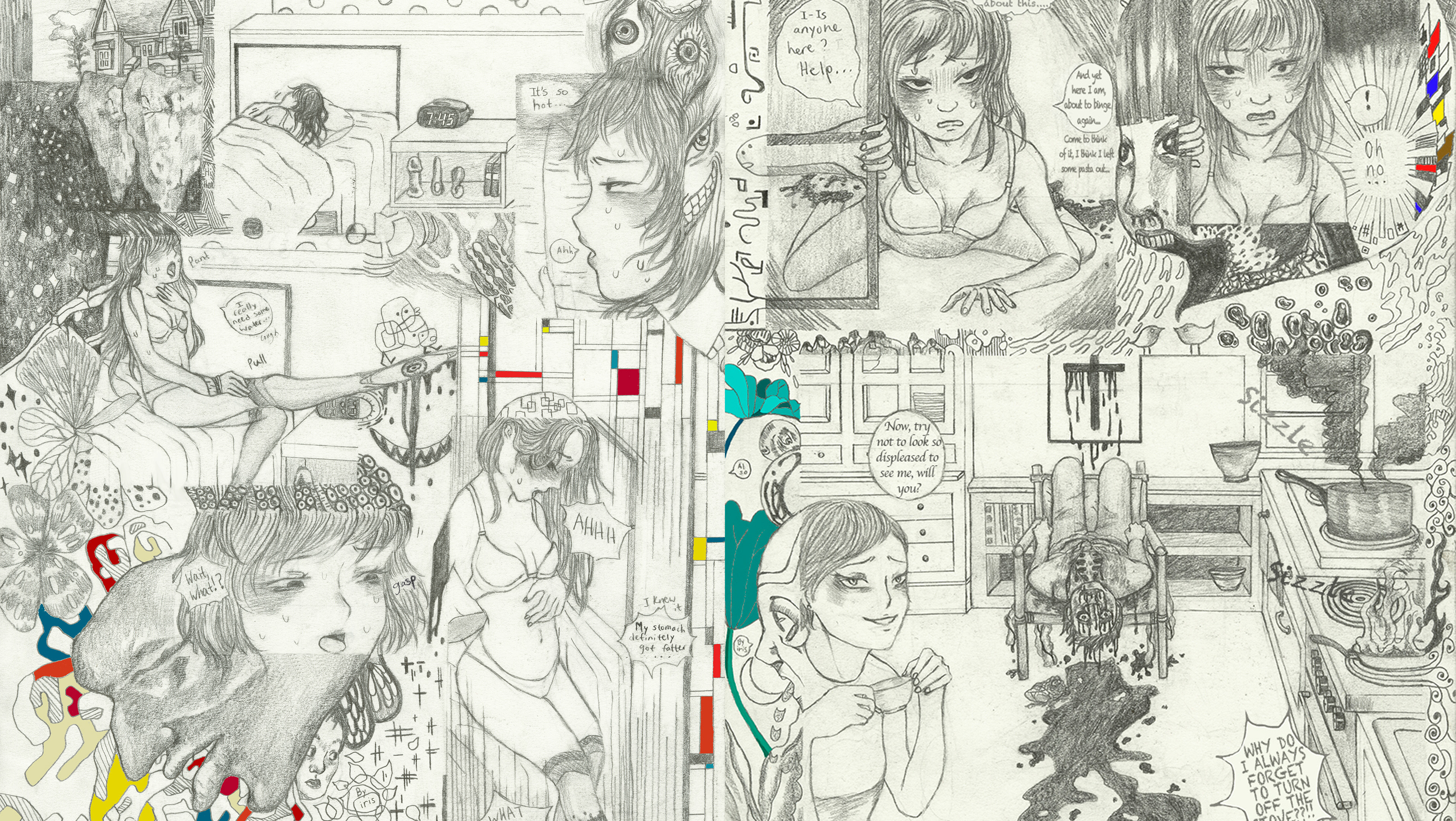

By reconstructing a narrative out of archival materials, ZÀO imagines answers to these questions the only way such a retrospective can: through collage, parody, and conspiracy. In other words — through strange fiction.

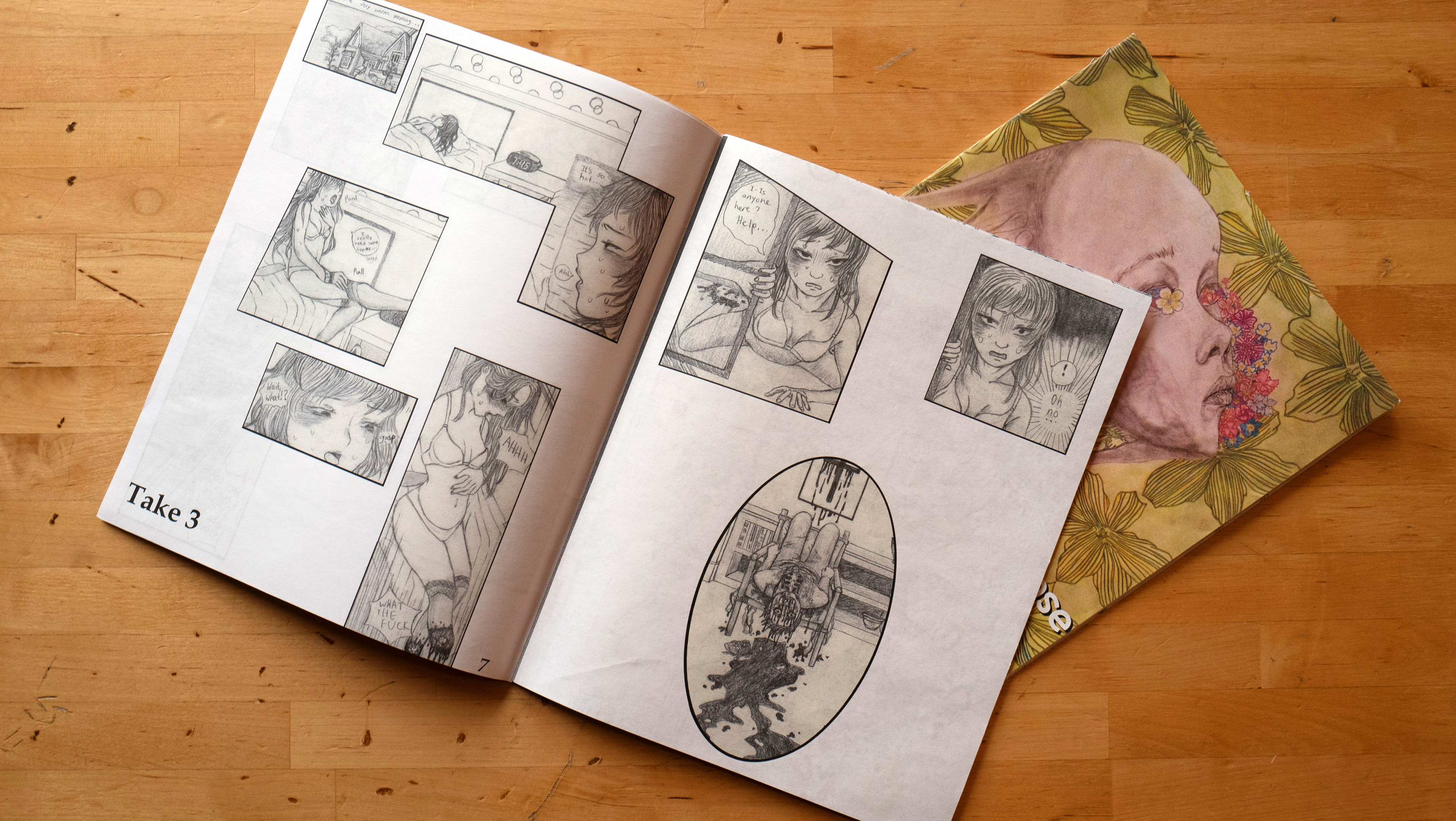

Each copy of ZÀO is paired with custom, double-sided bookmarks, designed especially to supplement the pages in which they are found.

The following four photos document ZÀO's exhibit in the 2019 showcase "RE:," at the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, Chicago, IL. The showcase included print copies of ZÀO, digitally-printed photo-boards of magnified double-spreads from ZÀO, a culinary-themed display with chopsticks, sugar, and signs stating "read at your leisure, with a grain of salt," and a webcomic version of ZÀO on the computer.

A visitor reading ZÀO's webcomic version.

The remaining images are all various double-spreads from volumes I and II of ZÀO, in chronological order.

The following images are all various double-spreads from volumes I and II of ZÀO, in chronological order.

Further Reading:

For a hefty, statistically-laden scholarly account of the Great Chinese Famine and the Great Leap Forward that instigated/exacerbated it: Yang, Jisheng. Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962. 1st American ed. Translated by Edward Friedman, Jian Guo, and Stacy Mosher. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012.

For a collection of short, personal stories from the Great Chinese Famine: Zhou, Xun. Forgotten Voices of Mao's Great Famine, 1958-1962: An Oral History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

For an overview and detailed accounts of violence during the Cultural Revolution: http://ywang.uchicago.edu/history/

To browse through a gargantuan but well-organized database of propaganda from mid- to late-20th century China, covering but spanning beyond the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution: https://chineseposters.net

For a taste of Mao's Mangoes: Murck, Alfreda. "Golden Mangoes: The Life Cycle of a Cultural Revolution Symbol." Archives of Asian Art 57 (2007): 1-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20111345.